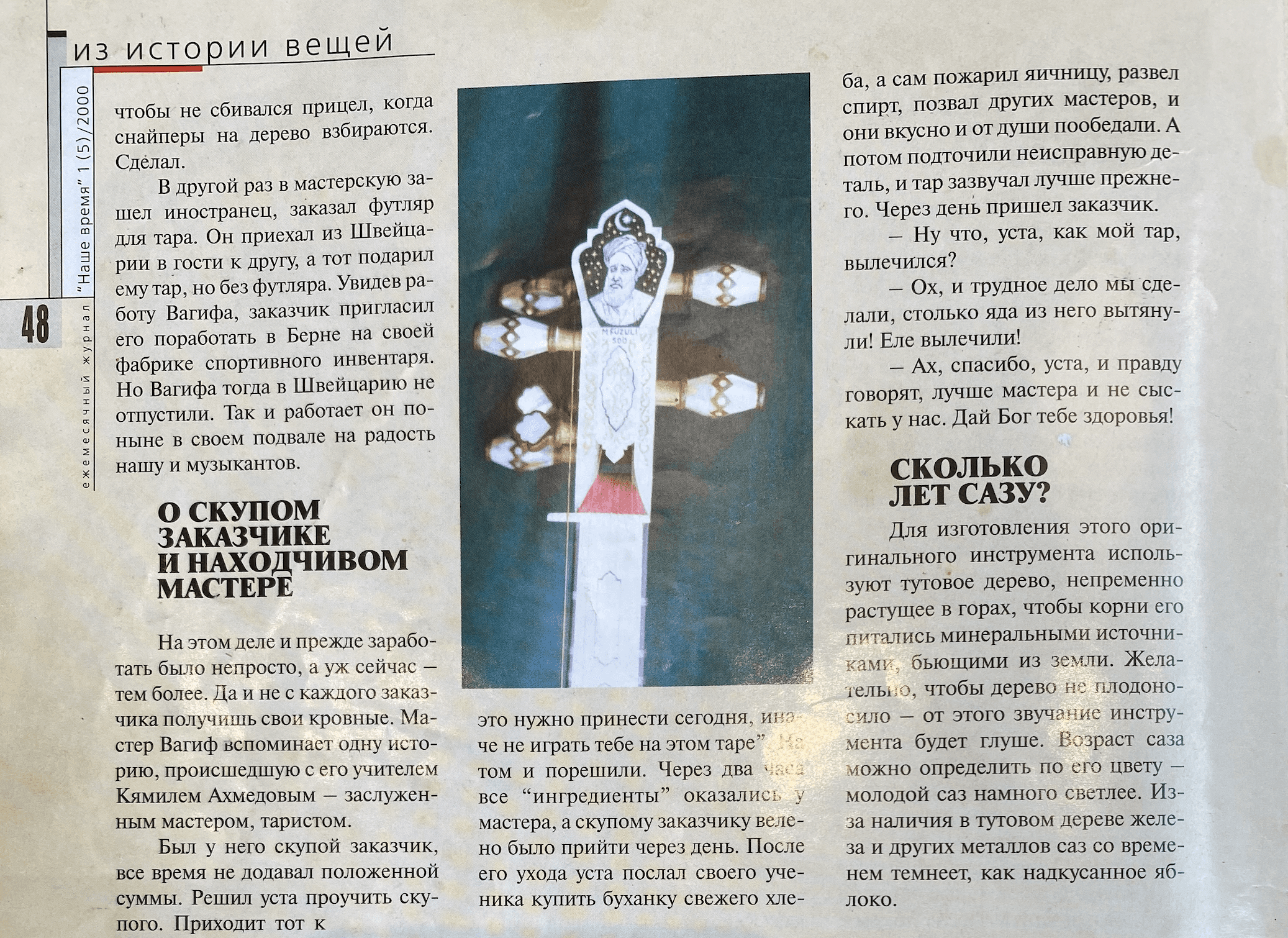

GERMAN "TRACE" IN OUR FOLK MUSIC

In 1989, upon joining the only workshop in Baku dedicated to the production of national musical instruments during Soviet times, Vagif initially started by making cases.

In the past, musical instruments in Azerbaijan were stored in canvas covers or simply in boxes, which created certain inconveniences and left the instruments largely unprotected from damage.

In the post-war period, a German prisoner of war named Wallenberg, a specialist in making cases, ended up in Baku. He developed the shapes of cases for storing kamancha, tar and other musical instruments.

To make a case, a solid wooden block is first prepared, which is then wrapped like a cocoon with dampened cardboard in 4-5 layers. The first layer is nailed to the block, and the subsequent layers are glued on top of each other. The case is then covered with faux leather, cut in half like a pear to form two parts, and the "core" of the block is removed. Finally, the inside is decorated with velvet, and locks and handles are added.

"This work is harmful, so during Soviet times, we were given milk for the hazardous nature of the job, and materials were also provided," Vagif laments. "Now I have to source everything myself. If only I had a decent workspace! Right now, I’m working in a basement with no natural light. My eyesight is already weak, and my hearing is also starting to fail."

Other craftsmen, Majid and Balabay, work from home, while Rajab Usta works at the N. Tusi University. If only they could be brought together in one well-equipped workshop! After all, there are only four craftsmen left in all of Azerbaijan, and they have no apprentices—the work is difficult and not profitable at all.

Master Vagif had to make more than just cases for musical instruments. Once, he received an unusual order: a high-ranking KGB officer needed cases for two sniper rifles that would prevent the sights from being misaligned when snipers climbed trees.

He made them.

Another time, a foreigner came to the workshop and ordered a case for a tar. He had come from Switzerland to visit a friend, who had gifted him a tar without a case. Seeing Vagif’s craftsmanship, the customer invited him to work at his sports equipment factory in Bern.

However, Vagif was not allowed to leave for Switzerland at the time. And so, he continues working in his basement to this day, bringing joy to us and to musicians alike.

About Cases for Sniper Rifles, a “Sick” Tar, and Much More

"In the previous issue of the magazine, we began our story about the fascinating Azerbaijani musical instruments—the tar and the kamancha—and the master who creates them. Today, Master Vagif shares with us new captivating stories from the 'life' of these musical instruments. So, let’s begin..."

About the Stingy Customer and the Resourceful Master

This line of work has never been easy to earn a living from, and now it’s even harder. Moreover, not every customer pays what they owe. Master Vagif recalls a story involving his teacher, Kamil Ahmedov, a renowned craftsman and tar player.

He had a stingy customer who never paid the agreed amount on time. The master decided to teach him a lesson. One day, the customer came to the workshop with his tar and said, "Take a look, master. Something's wrong—it doesn’t sound right anymore."

The master put on his glasses, examined the tar, turned it around in his hands, even tapped it with his tongue, and finally said,

"My dear friend, when your tar was still a tree, it was bitten by a poisonous snake. Now it’s been poisoned."

"What should I do, master? How can I cure my instrument? Please help me—I’ll give you whatever you need, just tell me," the customer pleaded.

The master replied, "You’ll need 10 fresh, high-quality homemade eggs, half a kilogram of pure butter, and, to neutralize the poison completely, half a liter of pure alcohol. Bring all of this today, or you won’t be able to play your tar again."

They agreed, and within two hours, the "ingredients" were brought to the master. The stingy customer was told to come back in two days. After the customer left, the master sent his apprentice to buy a fresh loaf of bread, fried up the eggs, mixed the alcohol, and invited the other craftsmen over. Together, they enjoyed a hearty and delicious meal.

Afterward, the master fixed the faulty part of the tar, and it sounded better than ever before.

Two days later, the customer returned.

"Well, master, how is my tar? Is it cured?"

"Oh, what a difficult task it was! We pulled out so much poison from it! It was barely saved!"

"Ah, thank you, master! They’re right when they say you’re the best craftsman around. May God grant you good health!"

"How old is the saz?"

For the creation of this unique instrument, mulberry wood is used, specifically from trees growing in the mountains, where their roots are nourished by mineral springs emerging from the earth. Ideally, the tree should not bear fruit, as this results in a more muted sound for the instrument.

The age of a saz can be determined by its color—a younger saz is much lighter. Due to the presence of iron and other metals in the mulberry wood, the saz darkens over time, much like a bitten apple.

The Legend of the Tar

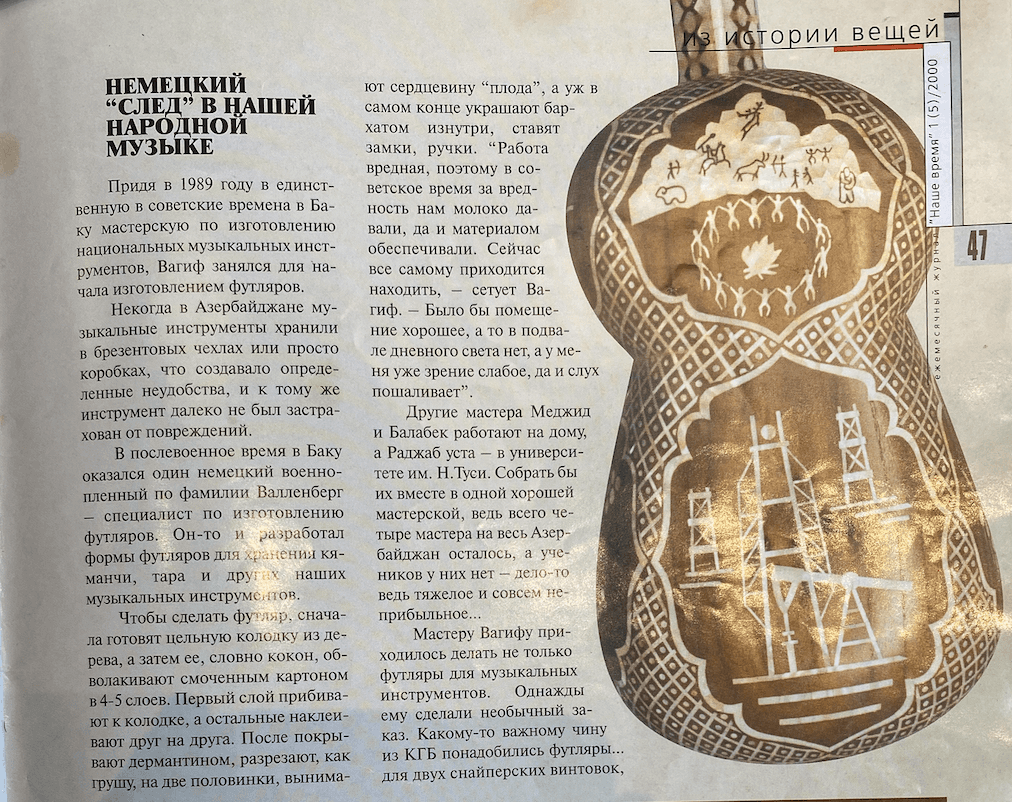

In ancient times, there lived a Musician who played an instrument crafted from a polished wooden log. Through his music, he could convey all his thoughts and emotions, and people easily understood his "language."

In those days, there was also a cruel Khan who could not tolerate anyone speaking ill of him. To silence "gossip," the Khan issued a decree: anyone who spoke badly of him would have molten lead poured down their throat.

People feared the Khan and chose to remain silent. Only the Musician continued to speak the truth in his unique musical language. Upon hearing about this, the Khan sent his vassals to punish the brave soul. But the Musician said, "It wasn’t me who spoke; it was the instrument."

After some deliberation, the loyal servants poured molten lead onto the musical instrument. This created holes—"wounds"—that were later covered with a membrane made from a bull's heart. And so, the Tar came into being.

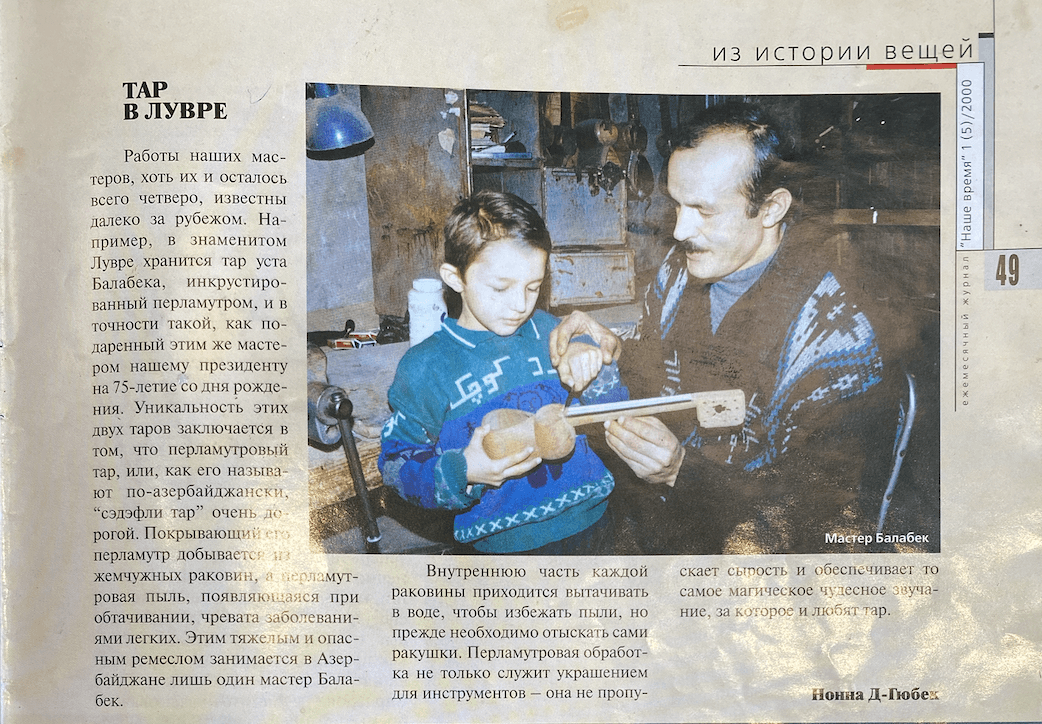

The Tar in the Louvre

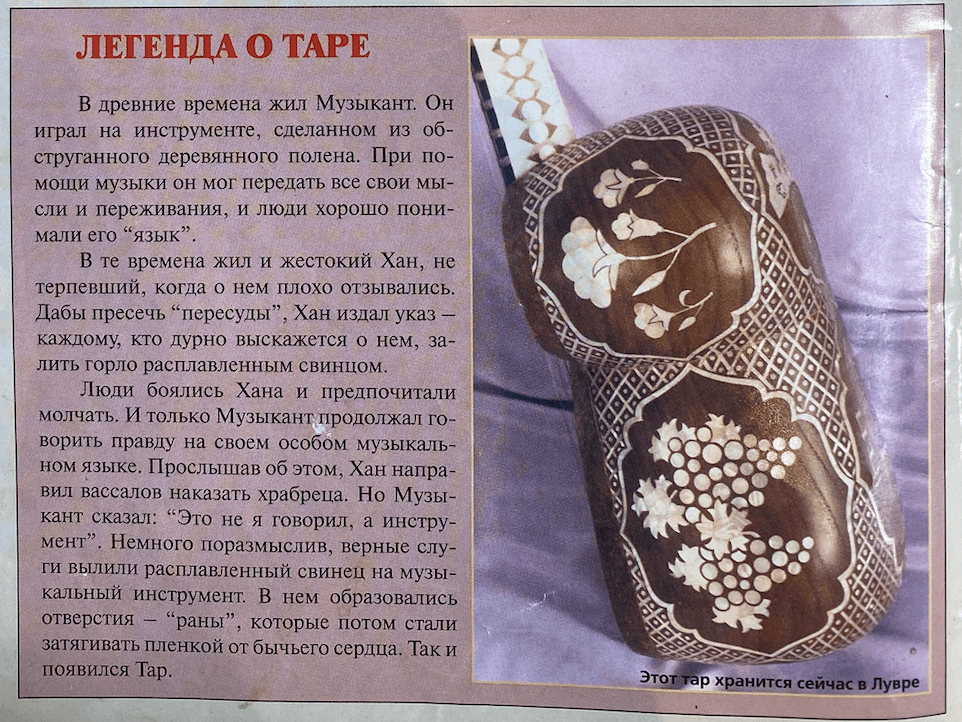

The works of our artisans, although there are only four of them left, are renowned far beyond our borders. For instance, the famous Louvre houses a tar crafted by Master Balabay, intricately inlaid with mother-of-pearl. It is identical to the one this master gifted to our president on his 75th birthday.

The uniqueness of these two tars lies in the fact that a mother-of-pearl tar—or, as it is called in Azerbaijani, "sədəfli tar"—is incredibly rare and expensive. The mother-of-pearl used to decorate it is sourced from pearl oyster shells, and the fine dust generated during its processing poses a serious health hazard, potentially causing lung diseases.

In Azerbaijan, this challenging and dangerous craft is practiced by only one master—Balabay.

The inner part of each shell must be carved under water to avoid dust, but first, the shells themselves have to be found. Mother-of-pearl inlay not only serves as a decoration for the instruments—it also prevents moisture from penetrating and provides that magical, enchanting sound for which the tar is so beloved.